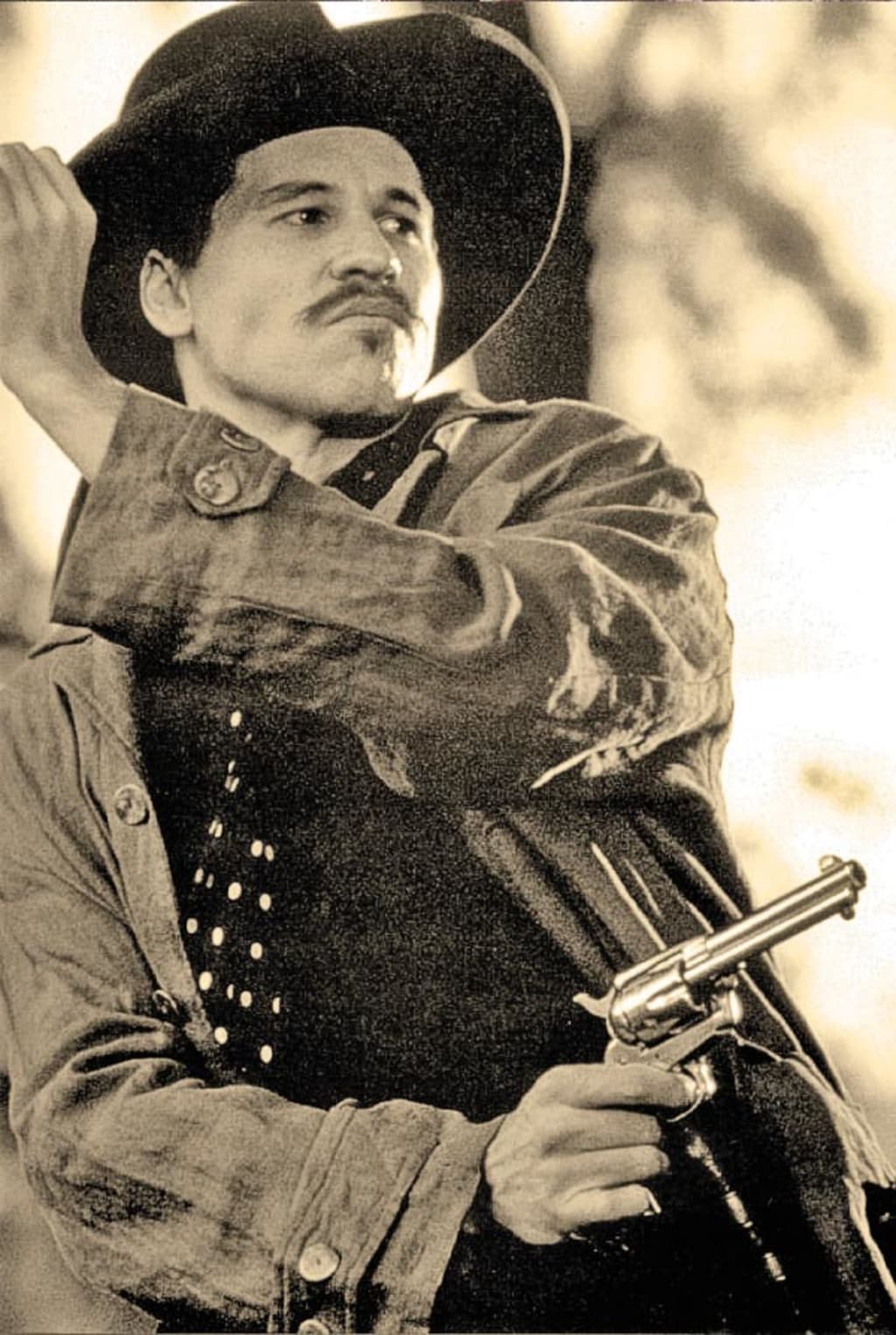

Doc Holliday Poker Scene

Posted By admin On 27/07/22By MICHELLE FLOYD

It's a shoot-out that has come to represent the glamour and gore that defined the Wild West, or, at least, our modern-day understanding of it.Pitting a motley crew of unconventional lawmen — the Earp brothers and Doc Holliday — against the so-called Cochise County Cowboys, the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, was over in less than 30 seconds. Doc Holliday: Maybe poker just isn't your game. I've got an idea let's have a spelling contest. I've got an idea let's have a spelling contest. Doc Holliday: I have two guns, one for each of ya.

Arizona Sonora News

But the best poker-related articulation of Holliday’s perspective comes during a light-hearted scene when he manages to convince a skeptical Earp to back him in a poker game, explaining to the marshal how “like a lawman needs a gun, I’m a gambler” and “money’s just a tool in my trade.”. Directed by Leslie H. With Jack Kelly, Peter Breck, Alan Hewitt, Charity Grace. The czar of a frontier town has Bart thrashed to steal back his gambling losses, which angers even the boss' mother.

In the town that billed itself as being “Too Tough to Die,” the women were even tougher. Everyone has heard of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holiday and John Ringo . But have you heard of Big Nose Kate, Sadie Jo, China Mary, Margarita, and Dutch Annie?

Tombstone, 30 miles from the Mexican border and 70 miles southeast of Tucson, was one of the last boom towns in the fabled old American West. The 1881 “Gunfight at O.K. Corral” put the town on the publicity map after big city newspapers, looking for colorful narratives out of the exotic Old West, widely wrote about it and edged that thirty-second shootout into the history books.

But just up the street, the female workers in the town’s busiest business, the extensive red light district, may have an even more enticing story, and one that doesn’t get nearly as much attention as gunfights in the street or in bars. Maybe they should, some historians say.

The historic Bird Cage Theatre in Tombstone. The Bird Cage, now a museum, was a theater, poker parlor, saloon and brothel. Photo by Michelle Floyd / Arizona Sonora News)

At the far end of Allen Street from the O.K. Corral, stands the Birdcage Theater, which in its heyday during the silver-mine boom was a riotous combination of saloon, gambling hall, dancehall, theater, opera house, and brothel. But many desperate young women who couldn’t get a gig at the Birdcage stationed themselves in pitiful streetside shacks called “cribs.”

Tombstone history reenactor, James Zuvela, described these shelters as “double the size of an outhouse.”

One still stands today, located off of Allen Street.

These cribs lined a 12-block span of Allen Street. In the town’s heyday, 106 cribs were recorded (prostitution was legal and licensed). Pockets full of cash, scores of men — miners, cowboys in town for a bender — would be lined up on Allen Street to patronize the cribs.

Tombstone doesn’t hide that part of its past. In the Birdcage, there is a room that displays photos and memorabilia of the best known local prostitutes, including their town-issued licenses. But Tombstone in general does not highlight that ugly aspect of its past as it markets itself with reenacted gunfights and faux westernalia.

There are several museums in Old West towns that cogently highlight the era and its settings, while providing educational context about the exploitation of poor girls who had no other options and the role of prostitution in an Old West town. One of them is the Old Homestead House Museum in the historic gold-mine mecca of Cripple Creek, Colorado, where women in period garb conduct well-informed tours and the admission price is $5. One recent visitor raved on TripAdvisor.com: “The ladies who give the tours are superb! It feels like they knew the working girls personally. …The furnishings were so beautiful and they even gave their history!”

The Birdcage, by contrast, charges $10 admission.

The prostitution business boomed on sordid levels with prices often determined by perceptions of race, “Chinese, African American, and Native American women cost 25 cents; Mexican women were 50 cents; women billed as being “French” 75 cents, and American women went for $1.00,” according to Ben T. Traywick’s book, Behind the Red Lights (History of Prostitution in Tombstone).

Patty Feather gives an abridged tour of the entry room in the Bird Cage Theatre to visitors on Sunday, Sept. 18, 2016. Feather and her husband moved from Pennsylvania to Tombstone about two and a half years ago in search of “warmer and drier” weather. (Photo by Rebecca Noble / Arizona Sonora News)

Lacking freedom and money in big cities, some women journeyed to the Wild West for the same reasons as men —money, adventure, desperation to flee an old life and start a new one. But for women, becoming a cowboy, a miner or a sheriff wasn’t an option. Instead, thousands of women were drawn, and in some cased lured, to the Old West to work as prostitutes.

Many became trapped in wretched, desperate conditions where abuse and disease were rampant, and suicide was not uncommon. But some willingly chose to stay in the profession, and became prototypes for the kinds of Old West female characters often depicted as dancing girls or saloon keepers in cowboy movies and TV shows that coyly avoided mentioning the fact that the saloon keeper Miss Kitty in the long-running radio and later television series Gunsmoke would, in real life, have been a prostitute or a madam.

Many also took up residence in the Birdcage and several other venues, performing as both actresses in the limelight, and whores in the dim crIbs and tiny rooms downstairs or, as in the case of Tombstone’s venerable Birdcage theater, in balcony stalls in the theater itself.

The Birdcage was a gambling hall, a saloon, a whorehouse, a theater, and even a regional performing arts center that drew nationally touring acts, including opera singers and vaudeville hoofers. While culture was served, so were the demands of the male patrons, many of them cowboys or miners with pockets full of money on a night in town. There were 14 cribs or “bird cages” where the women would entertain men at all hours of the day, some downstairs by the poker tables and others in curtained off boxes above the theater itself.

Given that Tombstone has a well-documented problem drawing new tourists, especially young visitors who may not be especially enthralled by reenactments of gunfights, has the town neglected emphasizing one of its more compelling, and even colorful, historical legacies, though a sordid one — Old West prostitution and the ugly business it fostered? Why keep that aspect of its history from exploration at a time when few people under the age of 50 even know who Wyatt Earp was?

Susan Hawksworth, an employee of the Birdcage Theater, said the building’s racy past isn’t a secret to locals.

“Some people are shocked, but most people know about the prostitution,” she said.

Meet some of the ladies

Big Nose Kate, or Mary Katherine Harony, was one of the first madams to arrive in Tombstone, where the men admired her for her curves and her moxie. She caught the public’s eye as the on-again, off-again girlfriend of Dr. John Henry Holliday, A.K.A Doc Holliday.

Here is the grave of Dutch Annie, where she rests in Row 7 of the Boothill Graveyard on Sunday, Sept. 11, 2016. She was also nicknamed the “Queen of the Red Light District” and her death was mourned by both the rich and poor in Tombstone. (Photo by Michelle Floyd / Arizona Sonora News)

Kate stayed in Tombstone for a time until a fight with Holliday had her packing her bags and bloomers. She later went to work at a brothel out of town, but still came back to Tombstone to visit Holliday. The last time she visited Tombstone was the day of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, which she actually watched from Holliday’s bedroom while Holliday himself was shooting it out on the street.

Another woman who was involved with one of the men in the gunfight was Josephine “Sadie Jo” Sara Marcus. When she came to Tombstone, she became smitten with Wyatt Earp, the deputy marshal. Despite later movie and television depictions of Earp as a noble, steadfast lawman, Earp was a heavy drinker and a gambler who enjoyed the company of prostitutes.

Sadie Jo worked out of the Birdcage Theater as a prostitute between acting jobs. Before her and Earp’s love affair, Earp actually wrote her prostitution license, which had to be displayed above her bed for customers to see. These permits, issued by the city of Tombstone at the cost of $7.50, allowed women to run a “House of Ill Fame,” which was the actual wording on the document. They eventually fell in love and later on, Earp worked hard to hide her shady history.

Earp may have run the law in Tombstone, in the boomtown days, Mrs. Ah Lum, who was known as China Mary, was also a major figure. Her house still stands in Tombstone today. Many Asian prostitutes were known as “China Marys” at the time, but she was the China Mary of Tombstone.

She did not necessarily live a virtuous life. After all, she commanded prostitutes and even sold Asian slaves. But China Mary was well liked. Her funeral was attended by a big crowd. Her grave is in what is known as the Chinese section of the Boothill Graveyard, in the corner of Row 10.

One of the prostitutes whose life was marked by violence was called Margarita. As a Birdcage theater performer, she favored the poker-playing men, particularly Billy Milgreen. But Milgreen was the prostitute Gold Dollar’s man. When Margarita kissed Billy during a poker game, Gold Dollar stabbed her. She died that evening: Row 2 at Boothill graveyard.

Dutch Annie was a prostitute who earned the title of “Queen of the Red Light District.” She ran a house of “ill-fortune” in Tombstone, which was the designation for a prostitution house without a license. There is also evidence that she may have purchased one of her prostitution houses from Wyatt Earp.

Although she made a disreputable living, she was also admired kindness and charity, including taking care of miners when disease broke out through the camp. When she died, people from high social standing to those of red light world. mourned her death at Boothill, where she still rests today: Row 7.

This history of Tombstone is still visible in town today, for those willing to dig a little deeper beneath the gunfights and simulated bar brawls. But to many tourists, and even some in town who depend on tourism as a livelihood, Tombstone “is all about a 30 second gunfight to most people — and the history here is far richer than that,” said Tim Fattig, the manager at the O.K. Corral. manager.

Download high resolution images here.

Michelle Floyd is a senior Journalism Major at the University of Arizona, where she also plays softball. In her free time, she likes to be out hiking, hanging out with friends, and creating new media projects.

Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday were as different as night and day—or were they? Certainly they were exceptional friends in reality as well as in legend.

The story of the friendship of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday is the stuff of legend. Neither man’s story can be told without the other. Together, they fired the imaginations of storytellers in their own lifetimes and created a legend that eventually made the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral as resonant as the Battle of Gettysburg in the popular mind. Their devotion to one another is all the more dramatic because they seem so different. In the legend Wyatt Earp is portrayed as a cleareyed, stalwart lawman, tall, lean and calm—“the Lion of Tombstone”—who sees qualities in Doc others don’t. John Henry “Doc” Holliday, by contrast, is portrayed as a profligate, cold-blooded yet charming killer dying of tuberculosis who, nonetheless, is devoted to Wyatt. The contrast energizes the legend but leaves unanswered how two such different men could become friends in the first place.

They met in Fort Griffin, Texas, in the winter of 1877–78. There was nothing particularly memorable about it. Both were gamblers, one with a growing reputation as a hardnosed cow-town lawman, the other still honing the skills needed to survive in the backwater hellholes he had chosen for his trade. One looked the part of a frontiersman, tall and sure of himself; the other looked out of place, though he already had a reputation as a man who would not back away from trouble. Thin, almost frail, with a persistent cough and a soft Southern drawl, Doc was a mystery. The two of them only had time for an introduction before Wyatt moved on.

Holliday and his paramour, Mary Katherine Horony (aka “Big Nose Kate Elder”), left Texas for Dodge City, Kan., in the spring of 1878 to take advantage of the upcoming cattle season. Doc found something there he had not known since leaving behind his native Georgia and his family. He found a place in a circle of acquaintances whose lives would be linked to his through the years that followed. Bat Masterson, one of them, recalled, “During his year’s stay in Dodge at that time he did not have a quarrel with anyone, and although regarded as a sort of grouch, he was not disliked by those with whom he had become acquainted.” Holliday’s absence from police dockets and newspaper reports underscored his good behavior.

“It was during this time that he also made the acquaintance of Wyatt Earp,” Masterson added, “and they were always fast friends ever afterwards.” Wyatt himself explained why in a Tombstone, Arizona Territory, courtroom in the fall of 1881: “I am a friend of Doc Holliday because when I was city marshal of Dodge City, Kansas, he came to my rescue and saved my life when I was surrounded by desperadoes.”

In August and September 1878 several dramatic incidents occurred on the streets of Dodge between the Texas cowboys and the local police. In one of them Earp found himself facing a group of rowdy drovers alone. His pistol was holstered, and his life was in real danger. He recalled that Holliday was playing monte in the Long Branch Saloon when he looked out of the window and saw Wyatt alone and outnumbered. Quickly, Doc asked Frank Loving, the dealer, if he had a pistol. Loving gave Holliday a six-shooter from a drawer. Drawing his own revolver as well, Doc stepped onto the sidewalk and ordered the cowboys to throw up their hands. The move distracted their attention long enough for Wyatt to act. “In an instant I had drawn my guns,” he recalled, “and the arrest of the crowd followed.”

Earp never forgot that moment. Within weeks, though, Doc and Kate left Dodge for New Mexico Territory, in search of a healthier climate for Doc. They found relief in Las Vegas, a well-established community in that territory. However, Holliday returned to Dodge City in March and again in May 1879 to assist Masterson in the organization of a group of fighting men for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad during its dispute with the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad over the Royal Gorge in Colorado. In September 1879 Wyatt resigned as assistant marshal in Dodge to join his brothers in a move to Tombstone.

Earp reunited with Holliday in Las Vegas. They had seen each other only in passing for little more than a year, but when the Earp family pulled out for Prescott, Arizona Territory, Doc and Kate went with them. Holliday did not immediately follow them to Tombstone, however. Kate resented the Earps’ influence on her man and went to Globe, Arizona Territory, on her own, but Doc spent the next six months in Las Vegas and Prescott. In September 1880 he apparently decided to accept Wyatt’s invitation, although it is possible he was drawn there by a gamblers’ war involving other friends from Dodge and Texas. Whatever the reason, once Holliday was in Tombstone, his friendship with Wyatt and his brothers was sealed.

They could depend on Holliday. Doc stood by his friends in the gamblers’ war. He backed the Earps when William “Curly Bill” Brocius killed Tomb- stone Marshal Fred White in October 1880. He rode with Wyatt to Charleston, Ariz., to recover his stolen horse from Billy Clanton. He was on hand to help protect the life of gambler Mike O’Rourke (aka “Johnny Behind the Deuce”). He was prepared to ride with the posse that pursued the men who attempted to rob the Benson stage in March 1881. He was with the Earps in the Fremont Street fight (popularly and inaccurately known as the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral) with the Clantons and McLaurys that October. He stood with the Earps during the troubled times that followed. When gunmen crippled Virgil Earp from ambush in December, Doc backed Wyatt. In January 1882 Holliday braced John Ringo outside the Oriental Saloon and would have fought him had the law not intervened. He rode at Wyatt’s side as a posseman, and when Morgan Earp was assassinated that March, he joined the grueling vendetta ride to track down the men Wyatt blamed for the crime.

Holliday proved his loyalty, but he remained his own man. During his time in Tombstone he moved about freely, following gambling opportunities in other towns and visiting Kate in Globe. Wyatt did learn that being Doc’s friend came with a cost. The same trait that endeared him to Earp—loyalty —proved costly when it involved another friend, Bill Leonard, one of the Benson stage robbers. It not only made Holliday a suspect in the case, but also provided an opening for rumors the Earps were complicit in the robbery attempt. Accusations Kate made against Doc, and the more direct testimony of Ike Clanton following the street fight, kept the rumors alive. Holliday was also quick to take offense and to resort to gunplay when drinking, which resulted in several embarrassing incidents. His confrontation with Ike Clanton the night before the street fight drew some of the blame for that affair.

Doc became an embarrassment. Wyatt had enjoyed a reputation as an efficient police officer and had the support of Tombstone’s successful and respectable leaders. His relationship with Holliday troubled them. John P. Clum, Tombstone’s mayor during its troubled heyday and a lifelong friend of Wyatt, said plainly in 1929, “I never approved of Holliday.” District Court Justice Wells Spicer, in his decision following the street fight, took Chief of Police Virgil Earp to task for calling on a man of Doc’s reputation for assistance in the attempted arrest of the Clantons and McLaurys. Wells, Fargo & Co. defended Doc against charges he was involved in the Benson stage holdup yet described him as “a man of dissipated habits and a gambler.” Tombstone reporter Ridgely Tilden blamed Doc “for all of the killing, etc., in connection with what is known as the Earp-Clanton imbroglio.…He kicked up the fight, and Wyatt Earp and his brothers ‘stood in’ with him on the score of gratitude.”

Doc was now Wyatt’s Achilles’ heel. The vendetta prompted Earp’s critics to craft a major rewrite of the history of the Tombstone troubles, hinged upon Holliday’s reputation and alleged misdeeds. Doc’s lapses were “proof” the Earps themselves were criminals. The tactic put Earp’s associates on the defensive. Clum later reflected that without Holliday’s presence at the street fight, “the affair would have been relieved of much of its bitterness.” In Holliday’s absence, the Earps would have been easier to defend. Wyatt stood by Doc, nevertheless, and Clum knew why: “There is no doubt in my mind that Doc Holliday was loyal to his friends and a ‘dead game sport’ —whether he was playing poker or pulling the trigger.… He doubtless was a loyal friend.”

Still, Holliday’s behavior eventually took its toll. When the Earp posse fled Arizona Territory, Wyatt and Doc finally quarreled. In Albuquerque, according to that city’s Evening Review of May 13, 1882, Doc “became intoxicated and indiscreet in his remarks, which offended Wyatt and caused the party to break up.” Doc and Dan Tipton left the rest of the posse and headed for Colorado on their own. Doc brushed it aside later, saying simply, “We had a little misunderstanding, but it didn’t amount to much.” After a brief reunion at Trinidad, Colo., where Masterson served as marshal, Wyatt and a few others slipped away to Gunnison, Colo., to lay low until they could decide what to do next. Doc went his own way.

On May 14, 1882, Holliday left Pueblo for Denver in the company of several men he knew, including Masterson. He planned to rest a few days before moving on to the Wood River country in Idaho Territory, leaving the Arizona troubles behind him. Before he could do anything but announce his presence to the Denver authorities, however, he was arrested in bizarre fashion and became the center of an extradition controversy over papers filed to return him to Arizona on murder charges. Forces mobilized quickly on Doc’s behalf. Masterson was the front man, but it was obvious powerful men were working to keep him from being sent back. When asked if the Earps would help him, Doc said, “Yes, all they could; but they are wanted themselves and of course couldn’t go back with me without putting themselves in danger, without doing me any good.”

Eventually, Doc walked away a free man and joined the Earps in Gunnison. Smooth, controlled and charming in Denver, he fell back into bad habits at Gunnison. Policeman Judd Riley recalled, “Doc Holliday was the only one of the gang that seemed to drink much, and the minute he got hilarious, the others promptly took him in charge, and he just disappeared.” His behavior aggravated the already strained relationship with Wyatt. At midsummer they said goodbye. Wyatt and Warren Earp headed for California and a reunion with their family. Doc left Gunnison for Pueblo, to address charges tied to the deal that ended the extradition effort. He then went to Leadville.

Holliday had become notorious because of newspaper coverage during his arrest in Denver. Many in the press considered him the leader of the “Earp gang,” and a series of articles continued to pump up his image as a badman. The stories may even have helped Doc find a place in Leadville not unlike that he had known in Dodge City. He became involved in local politics and was singled out for his help in suppressing a fire that threatened the town. He even found members of the respectable community who enjoyed his company. Clearly, there was life after Wyatt Earp.

Doc may have seen Wyatt again in 1883. Earp was working in Silverton, Colo., when both Holliday and Bat Masterson showed up at the same time, just before the so-called Dodge City War, when a number of former Dodge City lights descended on the town in support of gambler Luke Short, who had run afoul of local authorities. Doc figured prominently in news accounts of the affair. His exploits, real and imagined, were reviewed in detail. Given Holliday’s past association with the crew that went to Short’s aid and his history of backing the play of friends, missing the party would have been uncharacteristic of him.

Doc’s health was failing by then and with it the skills and dexterity he needed to play cards or handle a gun. He was vulnerable in a whole new way. He drank to cope with his disease and his circumstances, and his temper led to a series of small encounters with the law. He learned then that some of his pals were fair-weather friends. Some took advantage of his misfortune. In August 1884 Doc shot Billy Allen, an ex-policeman and bartender. Allen survived, and Doc was acquitted in March 1885. Leadville seemed to approve the verdict, and Doc’s health recovered sufficiently that he was able to move to some of the other Colorado camps and even to leave the state. The winter of 1885–86 proved rough on him, and Masterson told a newspaper reporter that Holliday suffered from a bout with pneumonia, “which I am afraid is going to do him up.”

Doc Holliday Poker Scene

Wyatt, traveling with Josephine Sarah Marcus as his wife, was in and out of Colorado in 1884 and 1885, even operating a saloon for a time in Aspen, but he apparently made no effort to contact Doc. They did meet one last time at a Denver hotel in 1886. Josephine—“Sadie” to Wyatt—left the only account of that last goodbye. The Earps were sitting in the lobby when they saw “a thinner, more delicate-appearing Doc Holliday than I had seen in Tombstone” approaching them. Wyatt immediately got up to greet him, and they sat down nearby and talked for a while. “When I heard you were in Denver,” Doc told Wyatt, “I wanted to see you once more…for I can’t last much longer. You can see that.”

“My husband was deeply affected by this parting from a man who, like an ailing child, had clung to him as though to derive strength from him,” Josephine recalled with a revealing twist. “There were tears in Wyatt’s eyes when at last they took leave of each other. Doc threw his arm across his shoulder.”

Tombstone Doc Holliday Poker Scene

“Goodbye, old friend,” Doc said. “It will be a long time before we meet again.”

In August 1886, after Denver authorities arrested Holli- day for vagrancy, he returned to Leadville, where he still had friends. In May 1887 he moved to Glenwood Springs, Colo., hoping the springs would relieve his symptoms. He lingered through the summer and died there on November 8, 1887. Gamblers, saloonmen and other locals who had come to admire Doc’s “fortitude and patience” collected money to pay for his funeral. He was buried, the local paper said, “in the presence of many friends.”

The Leadville Evening Chronicle reported on November 10, “His friends in Leadville sent him a purse on Monday morning last by express, but ere it reached him, he had ended his eventful career here below.” On the evening he died, the Evening Chronicle noted: “There is scarcely one in the country who had acquired a greater notoriety than Doc Holladay [sic], who enjoyed the reputation of having been one of the most fearless men on the frontier, and whose devotion to his friends in the climax of the fiercest ordeal was inextinguishable. It was this, more than any other faculty, that secured for him the reverence of a large circle who were prepared on the shortest notice to rally to his relief.”

Doc’s final years provided important insights into his friendship with Wyatt. They put to rest the canard that Earp was his only friend. Their relationship was special because of what they had been through together, but Doc had other friends who enjoyed his good qualities, tolerated his bad habits and admired his courage in dealing with his mortal disease. The press gave considerable attention to both Holliday and Earp but devoted surprisingly little of it to rehashing the Tombstone troubles. The press did not muse over why they were friends, because despite their differences they were considered cut from the same cloth. Courage and loyalty and honor bound them and set them apart as “extraordinary characters.”

Doc left no interviews that provide clues about his friendships or feelings. Asked by a Denver reporter if he knew the Earps, he answered simply, “Yes, they are my friends.” That is all he needed to say. E.D. Cowen, a writer who knew him in Denver and in Leadville, explained, “He was too deeply sincere to be voluble of speech and too earnest in his friendships to make a display of them.” Lee Smith, another friend of Doc’s both in Georgia and in the West, summarized him: “He was a warm friend and would fight as quick for one as he would for himself. He did not have a quarrelsome disposition but managed to get into more difficulties than almost any man I ever saw.”

Wyatt’s life followed a different course. He gambled, dabbled in business and mining, and craved respectability. He hobnobbed with powerful and important men. He knew hard times and high times and lived long enough to see himself portrayed as both hero and villain. In the 1890s, especially after the Sharkey-Fitzsimmons heavyweight boxing scandal in San Francisco, Earp found himself smeared in a series of fanciful and negative articles by men like Charles H. Hopkins, Charles Michelson and Alfred Henry Lewis. The attacks eventually brought Wyatt’s friends to his defense.

In 1907 Bat Masterson wrote a series of articles for Human Life magazine on “Famous Gunfighters of the Western Frontier.” In his profile of Earp he wrote: “Wyatt Earp…has excited, by his display of great courage and nerve under trying conditions, the envy and hatred of those small-minded creatures with which the world seems to be abundantly peopled, and whose sole delight in life seems to be in fly-specking the reputations of real men. I have known him since the early ’70s and have always found him a quiet, unassuming man, not given to brag or bluster, but at all times and under all circumstances a loyal friend and an equally dangerous enemy.”

Masterson explained Wyatt’s friendship with Holliday by saying simply that Doc was “as desperate a man in a tight place as the West ever knew.” He was less charitable in his article on Holliday, describing Doc as “hotheaded and impetuous and very much given to both drinking and quarreling, and, among men who did not fear him, was very much disliked.” Masterson claimed: “Holliday had few real friends anywhere in the West. He was selfish and had a perverse nature—traits not calculated to make a man popular in the early days on the frontier.” Bat did note one saving grace: “His whole heart and soul were wrapped up in Wyatt Earp, and he was always ready to stake his life in defense of any cause in which Wyatt was interested.…Damon did no more for Pythias than Holliday did for Wyatt Earp.”

Masterson provided the standard explanation of the Earp-Holliday friendship, but it did not silence Wyatt’s critics. By the 1920s Earp was frustrated by the ongoing barrage of criticism in books and articles and worried about how he would be remembered. The stories grew wilder with each telling, and Doc’s part in the story seemed more and more a liability. Wyatt’s dilemma was apparent in his testimony at the Lotta Crabtree trial in 1925. Asked specifically about his relationship with Holliday, Earp claimed his enemies tried to injure him in every way possible and used Holliday’s reputation as one tool. “Whenever they would get a chance to shoot anything at me over Holliday’s shoulders, they would do it,” Wyatt said. “So they made Holliday a badman. An awful badman, which was wrong. He was a man that would fight if he had to.”

He was even more defensive with Walter Noble Burns, a writer interested in penning Wyatt’s biography. Wyatt was, at the time, involved in an ill-fated effort to produce a biography through his friend John Flood, who was well-intentioned but lacked skills as a writer. Burns offered an alternative, asking Wyatt to help him with a biography of Doc Holliday. On March 15, 1927, Wyatt wrote Burns: “I will give you what information you ask as near as I can. I would much rather not have my name mentioned to [sic] freely. I am getting tired of it all, as there have been so many lies written about me.” He denied Holliday was involved in the attempted robbery of the Benson stage. “He never did such a thing as holdups in his life,” he wrote, but added, “He was his own worst enemy.”

When Burns published Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest later that year, Earp felt betrayed, but Burns explained the friendship between Wyatt and Doc with an easy grace: “Between Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, as cold, deadly men, perhaps, as the frontier knew, existed a friendship classic in its loyalty. For his friend, the coldest-blooded killer in Tombstone risked his life time and again, and only the accidents of the fighting prevented his making friendship’s last supreme sacrifice. And what Doc Holliday gave in friendship, Wyatt Earp returned in a friendship as staunch.”

Stuart N. Lake, who succeeded Flood as Earp’s chosen biographer, by contrast, found “the extraordinary association” of Wyatt and Doc to be an “enigmatic wonder.” He passed if off with a quote attributed to Wyatt, “In the old days neither Doc nor I bothered to make explanations.” It rang true, but Lake was not happy with Holliday’s role in Earp’s life and consciously looked for ways to use Wyatt’s affection for Doc as evidence of his noble and selfless nature.

Josephine Earp, who had reasons to disapprove of Doc dating back to Tombstone, elaborated on that theme in her unpublished recollections. “Wyatt’s loyalty to the irascible tubercular was one of gratitude not unmixed with pity,” she wrote. Doc’s “mysterious attraction” to Wyatt was “more of a liability to the peace officer’s reputation.” But Doc had saved Wyatt’s life in Dodge City, she said, and Wyatt had been grateful. “My husband has been criticized, even by his friends, for being associated with a man who had such a reputation as Doc Holliday’s,” she wrote. “But who, with a shred of appreciation, could have done otherwise? Besides, my husband always maintained that the greater part of the crimes that were attributed to Doc were but fictions.… Wyatt’s sense of loyalty and gratitude was such that [if] the whole world had been all against Doc, he should have stood by him out of appreciation for saving his life.”

By then the issue was no longer the nature of the friendship but the reputation of Wyatt Earp. Holliday’s character had become the measure of Earp’s character. Wyatt’s contemporaries may have questioned his judgment in standing by Doc, and his friends may have seen the cost of the friendship. But they knew why Wyatt had befriended Doc. Holliday had saved his life, and such a debt had no expiration date. Not even Doc’s reputation or his misbehavior could trump it. When they parted ways in Colorado in 1882, it was not because their friendship ended. It was something much simpler. Wyatt no longer needed Doc to back his play.

Doc understood that. He did not see it as ingratitude. Both men knew that if Wyatt needed him again, Doc would be there. It was his way. Doc had backed not only Wyatt in Dodge City and Tombstone but also Bat Masterson in the Royal Gorge affair. He had backed his Dodge City friends in the gamblers’ war in Tombstone. He had joined his neighbors in fighting a fire in Leadville—no small thing for a consumptive in the mountains of Colorado. He had offered his services to Luke Short in 1883. Even Bat Masterson, later a harsh critic, said in 1886, “When I was sheriff in Dodge City I got to know him well, and there wasn’t a man in the whole place whom I would call on more quickly to uphold the law than ‘Doc’ Holliday.”

Men like Doc and Wyatt lived by a code that gave them security in a dangerous world. It was rooted in courage and loyalty. The question was not whether a man was “good” or “bad,” but whether he could be depended upon when trouble came. By the 20th century it was a value system that seemed odd or even imaginary, which is why many who lived it, or even observed it, romanticized it and nostalgically regretted its passing. Nineteenth-century standards of male friendship and notions of honor were different. Close male relationships were considered normal, manly and even ennobling. They certainly were not pondered as mysteries.

Such friendships were nonjudgmental and largely impervious to the opinions of others. Such friendships spoke for themselves. E.D. Cowen, Doc’s friend from Denver and Leadville, provided all the explanation needed in 1898: “This unique character of American daring and the acutest sense of fair play [was] full of sentiments easily touched but rarely spoken, incapable of abandoning a friend who had the law against him, and the bravest to execute the law when common sense dictated the justice of the decree.”

Georgia-based author Gary L. Roberts wrote Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend, which is recommended for further reading along with Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend, by Casey Tefertiller.

Originally published in the December 2012 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.